Left to right: June Goldsmith (director of administration, Internet Archive), Ted Nelson (creator of Project Xanadu), Brewster Kahle.

On a sunny autumn day, I walk among the pews of a former Christian Science church in San Francisco’s Richmond District. This ornate 1923 building houses the Internet Archive, a massive nonprofit library built for the digital era. While I know the Archive from its Web projects — like the Wayback Machine, which archives public Web sites — I’ve never met the people who run it. I’m in for a surprise.

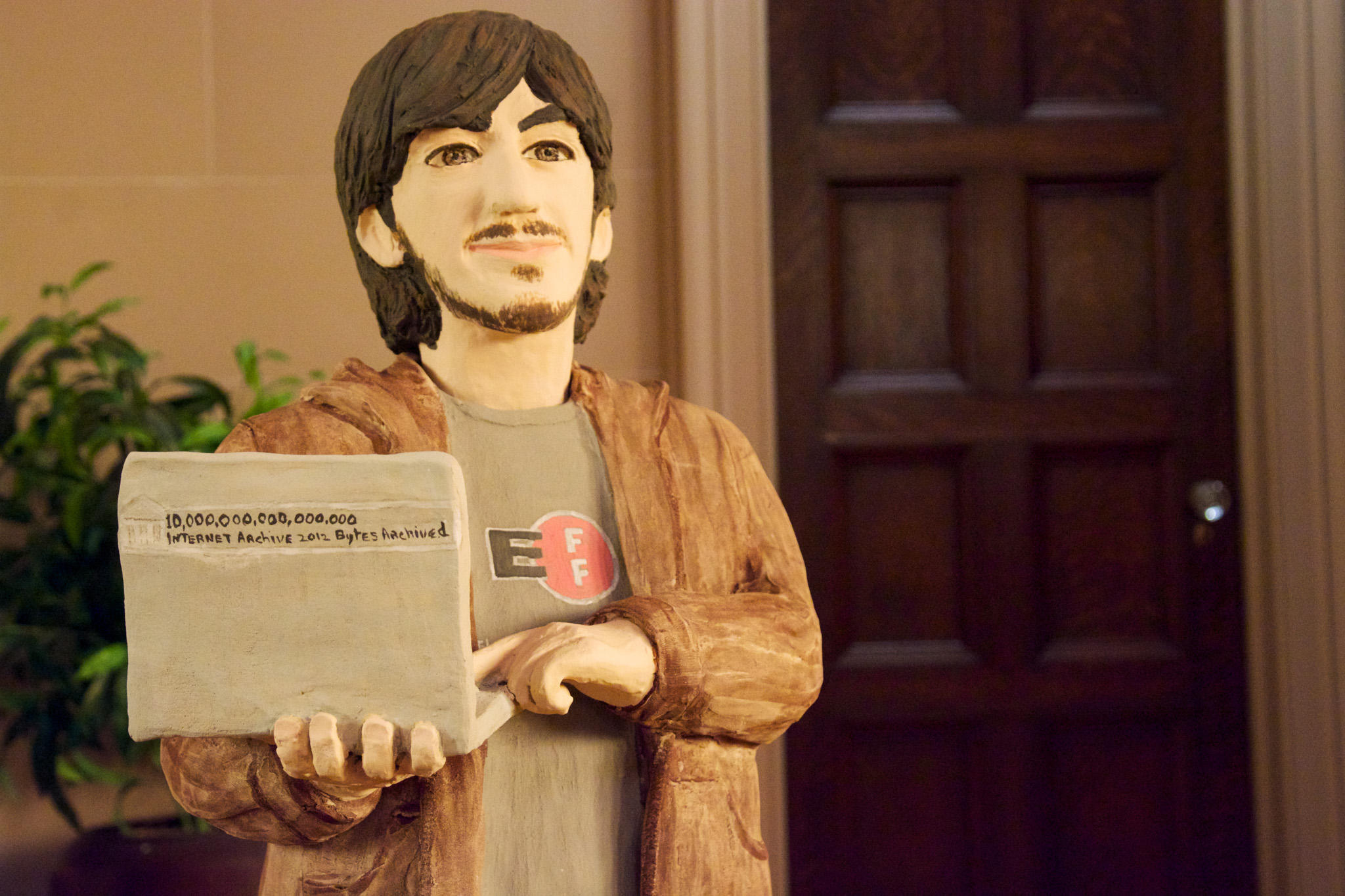

Rows of terra cotta statues stand in the pews, all facing a grand stage, while racks of servers (some of them used to host the Archive) blink in alcoves behind them. Each terra cotta “warrior” represents someone who has worked for or with the Internet Archive for three years or more, and they’re made by sculptor Nuala Creed. On the day I visit, they all gaze toward a lone figure onstage: Aaron Swartz.

Swartz helped create Open Library, one of the Internet Archive’s many projects, and he was inducted posthumously into the terra cotta army. His warrior bears an EFF (Electronic Frontier Foundation) T-shirt and holds a laptop with the inscription “10,000,000,000,000,000 Internet Archive 2012 Bytes Archived.” The warrior stands alone, looking over a house of worship now devoted to secular matters.

In this temple of knowledge, thousands of disks spin, scores of warriors stand guard, and dozens of archivists work to collect and catalog materials. They are creating a “library of everything.”

Aaron Swartz.

On the record

When I start my audio recorder in the daylight basement beneath the warriors, the first thing my interview subject says is, “I am Brewster Kahle, founder and digital librarian of the Internet Archive. It’s November of 2013. I’d love this to be public domain and would love an audio copy of this that I could post on the Internet Archive.”

When we finish our conversation, he pops the recorder’s memory card into his laptop and uploads the raw audio, pointing to status messages as our conversation flows into the public domain, preserved on racks of spinning disks on the floors above us, mirrored across the Bay, and partially mirrored in Alexandria and Amsterdam. This is the only time the unedited audio of an interview I’ve conducted has been shared publicly.

In Kahle’s act of instant uploading, I see one of the core principles of the Archive in practice: active archiving. Normally, an interview conducted for a magazine article would be preserved only in a private file (if it’s preserved at all), but the Archive is hungry, and its “digital librarians” walk the walk, pushing content into the system whenever possible.

Kahle and his merry band of archivists have set up more than 30 book-scanning centers in eight countries, pulling books into the digital realm and sharing them. The Archive contains over five million digitized books, all free to download in various digital formats. After scanning a book, the Archive saves the print edition, storing it in a climate-controlled shipping container. Each container holds an estimated 40,000 books, roughly equivalent to a typical community library. Kahle wrote, “The goal is to preserve one copy of every published work.” Although that goal cannot be reached, it’s the attitude that counts. When I ask Kahle about the endless nature of his archival task, he smiles and says, “It’s just everything.”

The Internet Archive hosts so many collections, it’s hard to keep track of them. The greatest hits are:

Wayback Machine, which keeps archival snapshots of Web sites reaching back to 1996.

Open Library, a digital card catalog that seeks to record metadata about every book ever published. (It has also become a digital lending library, pulling in ebooks from the Internet Archive and libraries around the world.)

Prelinger Archives, comprising thousands of films collected by archivist Rick Prelinger, who is also president of the Archive’s board of directors.1

Live Music Archive, TV News Archive, Buckminster Fuller Archive, Historical Software Collection, and the list goes on.

The Internet Archive is massive, currently containing more than 16 petabytes — 16 million gigabytes. It’s growing every day.

Naturally intelligent

Kahle chose his professional path while he studied artificial intelligence at MIT more than three decades ago. He recalled a crucial conversation: “A friend said, ‘Brewster, you’re an optimist and a utopian,’ and I said, ‘Yes.’ ‘And a technologist.’ ‘Yes.’ ‘Paint a portrait with your technology that’s better.’”

Kahle settled on two visions for what he could contribute: a library of everything, and an encrypted telephone system to protect caller privacy. He started on the encryption problem, figuring that others would build the library sooner or later. After designing encryption chips and failing to get the cost down to a practical level, Kahle was invited by his college friend Danny Hillis to work at Thinking Machines Corporation, the 1980s supercomputer startup, where a remarkable array of computer-science and straight science talent worked or consulted: Richard Feynman, Stephen Wolfram, Marvin Minsky, and a host of others.

Kahle was there, using his chip-design skills to help build, as the company famously claimed, “A machine that will be proud of us.” While at Thinking Machines, he helped create WAIS (Wide Area Information Server), an early system for searching online databases scattered around the Internet. Years before Thinking Machines folded, Kahle left to co-found WAIS, Inc., which he sold to AOL in 1995.

The next year, Kahle promptly co-founded a pair of companies: the nonprofit Internet Archive and the for-profit Alexa Internet. Alexa crawled the Web and derived patterns, including rankings of the most-visited Web sites. Alexa also had a unique contract with the Internet Archive, which stipulated that its Web-crawling data would be shared with the Archive after a six-month delay. That data seeded the Wayback Machine, and the contract remains in place today, even though Alexa was sold to Amazon in 1999.

Kahle designed Alexa and the Archive to fit neatly together. “For-profit companies come and go; they just don’t last, but they’ve got this energy.” He wanted the Archive to be boring and persistent: “a wholesaler…a repository, preservation-oriented.” Nearly two decades later, the plan has worked — although the most interesting libraries powered by the Archive are not run by Alexa, but are spin-offs from the Archive itself.

Today, Kahle reflects on the value of the Internet Archive in the context of the supercomputers he once built at Thinking Machines. “When we were starting an artificial intelligence, it felt like we were data-starved, that if we were going to build a thinking machine, if we’re going to build a machine that’s interesting to interact with, something that’s worth talking to, it should at least have read the great books!”

Thanks to Kahle’s optimistic vision, humans and supercomputers alike can freely read the classics. In fact, at a presentation given at the Long Now Foundation in 2011, Kahle suggested that many “readers” of these books will be computers, digesting data for humans to consume via search engines and the like.

Gleaning from an endless stream

The Internet Archive uses attention as one signal when deciding what materials to archive. Kahle says, “We look for YouTube videos that are mentioned in tweets as a mechanism of knowing that this is a video that somebody cared enough about to broadcast to some community.” Because YouTube is vast and hard to crawl, the Archive gleans sparingly.

Kahle also believes that an archive is only useful if its contents are accessible to the public. The Archive serves millions of users, who download 10 to 15 million books each month, among many other digital goodies. But many archives are “dark,” meaning that their contents are locked up in a basement somewhere. While those items may be preserved in one sense, they’re simply not available for the average person to use.

The notion of maintaining a massive, publicly accessible repository requires that the Archive handle all the legal and technical burdens involved in hosting and serving that content.2 But making materials accessible is the only way to allow readers to love them. Kahle says, “The key to preservation, I think, is access, which is not an obvious thing; it’s not what’s taught. People always talk about acid-free paper, fire-suppression systems, endowments, or whatever. It’s access. If things aren’t accessed, it’s not going to be loved. If it’s not loved, it’s not going to be cared for.”

Roger Macdonald, who directs the Television Archive, speaks to the cultural value of archiving TV news. “We have no way of reflecting back upon this most persuasive medium that just sweeps over us.” The Archive has been recording TV news programming around the clock since the year 2000, occasionally releasing special collections like the September 11 Television Archive. The Archive is about to receive a massive collection of 140,000 VHS tapes of TV news recorded at home from 1977 to 2012 by librarian and TV news producer Marion Stokes. It will take years to digitize, and Kahle estimates that the VHS tapes will fill three 40-foot shipping containers.

Recording and sharing TV shows presents legal challenges; the Archive allows users to view and share short clips online, but requires them to borrow a DVD in order to access an entire broadcast. Still, short clips can go a long way. For years, The Daily Show with Jon Stewart has refined the art of comparing and contrasting TV news clips in order to make a point. Archive engineer Tracey Jaquith recently developed a new interface to explore the massive TV dataset, giving Archive users a practical way to reflect upon the medium.

She demoed the interface in late October 2013, showing how it’s now possible to search TV using closed-caption text. Searching video from C-SPAN, she found the first time Senator Ron Wyden hinted at the NSA’s domestic surveillance programs. She grabbed the TV clip and posted it on her blog with her own commentary. She told the audience seated in pews, “Maybe one of you will become the next Jon Stewart.”

Fire in the reading room

Just days before my visit to the Internet Archive, a fire gutted a small scanning center attached to the main building that used to be the Reading Room when it was a Christian Science church. The fire broke out at night and didn’t harm the main building (or any people), but a smoky odor lingered in every room of the Archive, even with industrial air filters running around the clock.

Kahle takes a long view on how the Archive will react to the fire. “Let’s go in and design for it. If fires happen, okay, how do you go and make it so that you either minimize the loss or make it so that you can lose parts and you don’t lose the whole?” The irony of a digital archive going up in smoke isn’t lost on him. He sometimes refers to the Internet Archive as the “Library of Alexandria 2.0,” and indeed he named Alexa after the original Library of Alexandria. He points out that in the history of libraries, there is one persistent fact: they burn.

Alexis Rossi, who manages many of the Archive’s collections, puts the fire in context. “It’s one of 30 scanning centers. So I think the biggest thing for us is it really proves that digitizing things and making copies of them and sharing those copies with other people in the world keeps things safe. It keeps things alive.”

Since the fire, the Archive has seen donations skyrocket, as the community chipped in to help rebuild. Rossi continues, “It’s been heartening to see that what we’re doing really does matter and really can save data and make sure that content lives for future generations. It’s not just going up in flames.”

As I left the Internet Archive, I spotted a flag flying from a pole above its lawn. The flag features a version of the famous Blue Marble, a photograph showing the Earth from space. It seems appropriate that the library of everything does not fly its own flag; instead, it flies the flag of the Earth itself. When I searched the Web for the history of that flag, I came across a jingoistic 1938 educational film explaining the US flag’s history. The film was, of course, hosted by the Internet Archive.

Photos by the author.

-

Prelinger Archives was the first non-Wayback Machine collection hosted by the Internet Archive. Kahle convinced Prelinger to give away a chunk of his film archive for public consumption online, and it rapidly became a marquee part of the Internet Archive. The relationship between Prelinger’s work and the Internet Archive is so complex, there’s a disambiguation page explaining the nuances. ↩

-

Kahle’s early interest in individual privacy is still in full force at the Internet Archive. The Archive doesn’t log the IP addresses of its users, and recently implemented optional access via SSL/TLS encryption, which prevents easy sniffing of what users are viewing in a Web browser. ↩

Chris Higgins writes for Mental Floss, This American Life, and The Atlantic. He was writing consultant for Ecstasy of Order: The Tetris Masters. His new book is The Blogger Abides: A Practical Guide to Writing Well and Not Starving.