On June 19, 1976, the Grateful Dead played the Capitol Theatre in Passaic, New Jersey, kicking off the first set with a great run of “Help on the Way” > “Slipknot!” > “Franklin’s Tower” > “The Music Never Stopped” before launching into a spirited version of “Brown-Eyed Women.”

I know the show well, but not because I was there. I was on the other side of the country that night — not to mention being just two years old and change.

I know it because I’ve listened to a recording of the show many times. It was recorded by fans when it was broadcast live on WOUR Utica and WNEW New York, and a soundboard recording also circulated.1 This and thousands of other concerts by a multitude of artists are part of my collection of live music, amassed in various formats over the past 20 years and aided by a changing trading scene that’s gone both digital and online.

The legality of these recordings is varied and complex. Many bands, including the Grateful Dead, are known as taper friendly and happily encourage fans to swap recordings. Others explicitly prohibit the practice. Then there’s a large gray area in the middle, where bands tacitly allow taping and trading to go on. And in the past few years, bands themselves have gotten in on the fun by releasing official live recordings.

Behind the music

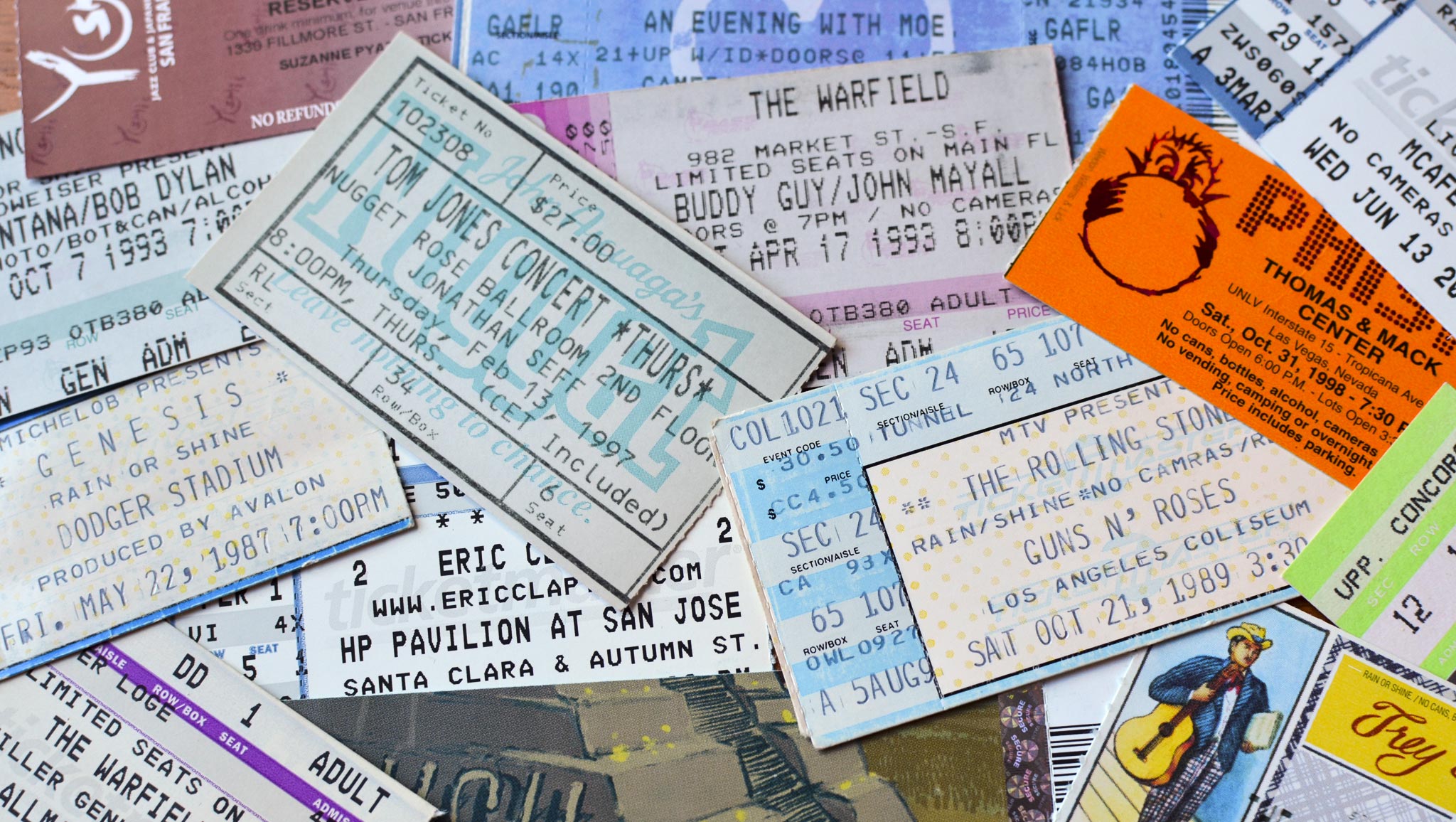

I love concerts. Sitting (or more often, standing) with hundreds or thousands of like-minded people and listening to a small slice of music history has always excited me. Recordings of live shows are obviously not the same, but they do give me similar pleasure. There’s just something ineffable about hearing a band as they were on a particular date, warts and all, including the stage banter, flubs, and musical selection.

I stumbled on live music trading in the early 1990s, when tracking down shows was challenging and trading was tedious. I specialized in the Grateful Dead then. Trading was free except for the cost of making a tape to swap with someone. We never thought of it as ripping off the artists because no money changed hands, and because of the sheer effort it took to make a trade.

The rules for making copies were strict: Always record in real time (my dubbing deck had an off-limits “double speed” button), note the set list and analog generation (increased by one with each copy) on the tapes you were sending, and never use any Dolby noise reduction while recording.

You started by digging up traders’ lists to see what recordings you wanted. True swaps were simple: You agreed on an equal number of cassette tapes, and each party sent them on their way at their own expense. But if you were just starting out, you hoped that a trader was nice and would allow a B&P, or blanks and postage, trade. You sent blank cassettes or CDs, along with a pre-addressed and stamped return envelope. All the other person had to do was make the copies, seal them up, and drop your package in the mail.

I wound up on the receiving end of many a B&P request, and I can’t tell you how often people would forget to include a note about what I was supposed to be copying, or even send cash and expect me to go to the post office and buy postage. (Because of these experiences, I added to my trading list a whole section of B&P rules that I expected people to follow.)

Cassettes slowly gave way to DATs2 and CDs. I even picked up a Tascam DA-20mkII to transfer and share some shows that I attended and couldn’t find in other formats, like a John Mayall/Buddy Guy show at the Warfield from April 17, 1993. At one point, a move prompted me to give away the bulk of my hundreds of cassettes. I kept a few that I just couldn’t bear to part with, including my friend’s stealth recording of a Black Francis (a.k.a. Frank Black) show we saw together at McCabe’s Guitar Shop in Santa Monica on March 22, 1991.

But for many people, CD trades waned relatively quickly when downloads became feasible. The links for downloads first showed up in IRC channels, and required using Hotline or FTP servers with a restricted number of logins. If too many people were downloading at once, you’d have to try again and again to get in.

Then BitTorrent came on the scene and downloads exploded. With the rise of distributed downloading and increased bandwidth, lossless audio files became the law of the land3 — first SHN (Shorten) and then FLAC (Free Lossless Audio Codec), with the odd APE (Monkey’s Audio) file thrown in.

BitTorrent trackers such as bt.etree.org, DIME, and the Trader’s Den have become the go-to sites for free downloads of new and vintage recordings. The sites’ rules vary, but most generally respect the wishes of artists when it comes to what is and isn’t kosher: If asked, they will remove commercially released tracks from any performance they host. And certain bands, like the Allman Brothers Band, are cool with people trading CDs of their shows, but explicitly disallow posting them online for download.

Listen to the music

When I was 15, I went to see Living Colour, Guns N’ Roses, and the Rolling Stones play in front of 90,000-plus fans at the LA Coliseum — it’s still the biggest show I’ve been to. The most memorable part of the night — outside of the performances — came when a few no-nonsense cops hauled away a friend who had been trying to record the show.

They thought he was rolling a joint, not fiddling with a tape recorder (this was 1989). When they discovered he was just an underage bootlegger, the response was, “Oh, you can’t do that either,” and they confiscated the tape before releasing him from under the belly of the beast that hosted both the 1932 and 1984 summer Olympic games. He was allowed to return to his seat, to the cheers of those sitting around us.

That experience gave me a lot of respect for tapers, whether they’re surreptitiously grabbing audio for trading (not sale) or out in the open, taping with the bands’ permission. For stealth recordings, it’s because of the risk involved. For allowed recordings, it’s because of the dedication: buying expensive mics and pre-amps, coming early to set up, monitoring the signal instead of dancing and enjoying the show (although they probably enjoy taping), transferring to computer, uploading to share with the community, and so on.

Many shows available for torrenting — especially on DIME and the Trader’s Den — are known as ROIOs, or Recordings of Indeterminate (or sometimes Independent) Origin. You know, bootlegs. But that term more specifically refers to an unauthorized recording. The idea behind sites like these is that nobody is profiting from the work of others; people share recordings with a community of like-minded fans (and sometimes the truly fanatical) with the understanding that they are never to be bought or sold.

Indeed, the disclaimer at the bottom of the DIME home page reads, in part, “BTW, the ROIOs exist, you can’t make them vanish. So, why not let your fans get them for free from one another instead of having to purchase them from commercial bootleggers on auction sites?”

The Internet Archive’s Live Music Archive offers an amazing collection of direct downloads and streams of more than 4000 artists and bands. Bands have the final say on whether their recordings get archived there. There are notable holdouts — such as Phish, who allow taping and trading of their shows in many other ways and sell shows directly to fans.

The real thing

There are thousands of great recordings circulating, from audience (AUD) recordings to soundboard (SBD) patches to radio (FM) broadcasts. A relatively new entry in the field is official SBD recordings.

Phish, for example, sells shows mere hours after the last note of the encore is played. It offers them in many different formats — MP3, FLAC, FLAC HD (24-bit, 48 kHz), Apple Lossless, Apple Lossless HD — as well as on CD. Most Phish shows (depending on the tour and venue) have an added treat: Ticket holders receive a free MP3 download of the show they attended, usually available by the time they get home.

The Live Phish site is powered by Nugs.net, which helps lots of bands sell their live shows to fans. Its LiveDownloads site sells shows from Gov’t Mule, moe., the Black Crowes, Ratdog, Crowded House, Metallica, Pearl Jam, Red Hot Chili Peppers, and many others.

The Allman Brothers Band sells both SBD downloads and CDs of their live shows.

Interestingly, even while they sell their shows, most of these bands still allow fans to set up giant mic stands and record every note to post freely for download.

Concert Vault offers streams and downloads of concerts — purchased from the archives of Bill Graham Presents — recorded between 1965 and 1999 from a staggering array of artists. Best of all, a membership (starting at $3 a month or $30 a year) gets you a free weekly download chosen by the staff. Some recent gems: Santana and Janis Joplin shows from the Fillmore East (1971 and 1969, respectively), U2 in Boston in 1987, and Ray Charles from the Newport Jazz Festival in 1960.

Collection or obsession?

I used to burn every show to CD to listen to on a stereo or in the car, but that became unwieldy. (I still have several boxes full of CD-Rs in jewel cases with printed labels and cover images I pulled from the Web.) Now, I burn backups of the lossless audio files to data DVDs, and I scan and catalog their contents with NeoFinder so I can find them in the future. I have a lot of those, too — at last count I was north of disc 1250 — but in paper sleeves and labeled with just numbers, they’re much more manageable.

Using a few different software audio players on my Macs, I can listen to the downloads at work. (Alas, not on iTunes, which doesn’t support any lossless format but Apple Lossless.) But I can also convert files to MP3s and put them on a flash drive that plugs into my car stereo. In the case of SBD recordings I purchased from bands, I usually download the MP3 versions so they’re ready to listen to in the car. They’re also a few bucks cheaper. Nothing gets the commute to work started right like a great live version of moe.’s “Buster” or Phish’s “Chalkdust Torture.” My Twitter stream can attest to that.

A goal of mine has been to find a recording of every concert I’ve been to. Many were easy to get because they were from taper-friendly bands like Phish, the Grateful Dead, Gov’t Mule, Ratdog, and the like. Some were hard-fought — like my first show, finally acquired thanks to help from the operator of the Genesis - The Movement site. And some remain elusive.4

A change is gonna come

The transition from snail-mailed cassettes to high-speed BitTorrent downloads has changed the nature of trades. For one, it’s made it much easier for anyone with a decent Internet connection and basic understanding of P2P file sharing to access a treasure trove of live music. As a result, I’ve now amassed over 6000 recordings. And with official downloads becoming more prevalent, the quality of the recordings is high.

At the same time, it’s made the whole process much less personal. As with ATMs replacing bank tellers, there’s less human interaction. I built up friendships with several tapers and traders over the years as a direct result of our one-to-one dealings. Now the level of dialogue rarely goes beyond posting comments on download pages (mostly thank yous, with the odd bit of snark).

And with official downloads, the relationship has changed from being between fans and tapers to being between fans and bands. Which, in many ways, makes a lot of sense since it’s their music in the first place.

It’s still an exciting time to collect live music. Every week there’s, say, a new lossless download of an early ’70s Pink Floyd show from a lower-generation tape with more complete tracks. And for a live music geek like me, that’s music to my ears.

Photo by Jon Seff.

-

Soundboard recordings are made by plugging into an audio jack on the mixing console used for the concert, whether that board is just handling the sound for the event’s live amplification, or a mix from the board is being taped by the band or promoters for later use. ↩

-

The Digital Audio Tape format never really took off broadly in the U.S., even though it had vastly higher quality than analog cassette tapes. A combination of expense and music-industry lobbying kept it from being a real presence in the market outside of the taping community and audio professionals. ↩

-

Lossless audio reduces the size of an uncompressed AIFF or WAV file by from 40 to 60 percent without tossing out any information. It finds patterns of redundancy and replaces those patterns with shorter symbols. Lossless formats are just like a zip file: Smaller than the original, but when you expand it you have the identical data you started with. Lossy MP3 or AAC files do discard information to shrink files, although they are designed to throw away the least noticeable elements of a recording. ↩

-

Still looking for these if you happen to have them: Billy Joel 04-03-1990 LA Sports Arena, Kula Shaker 04-02-1997 Fillmore, James Brown/Tower of Power 05-16-2000 Paramount Theatre, Jimmy Smith 05-08-2001 (Early) Yoshi’s, Van Halen 08-10-2004 HP Pavilion. ↩

Jonathan Seff is an avid crossword solver, father of twins, and veteran technology journalist currently looking for his Next Big Thing.