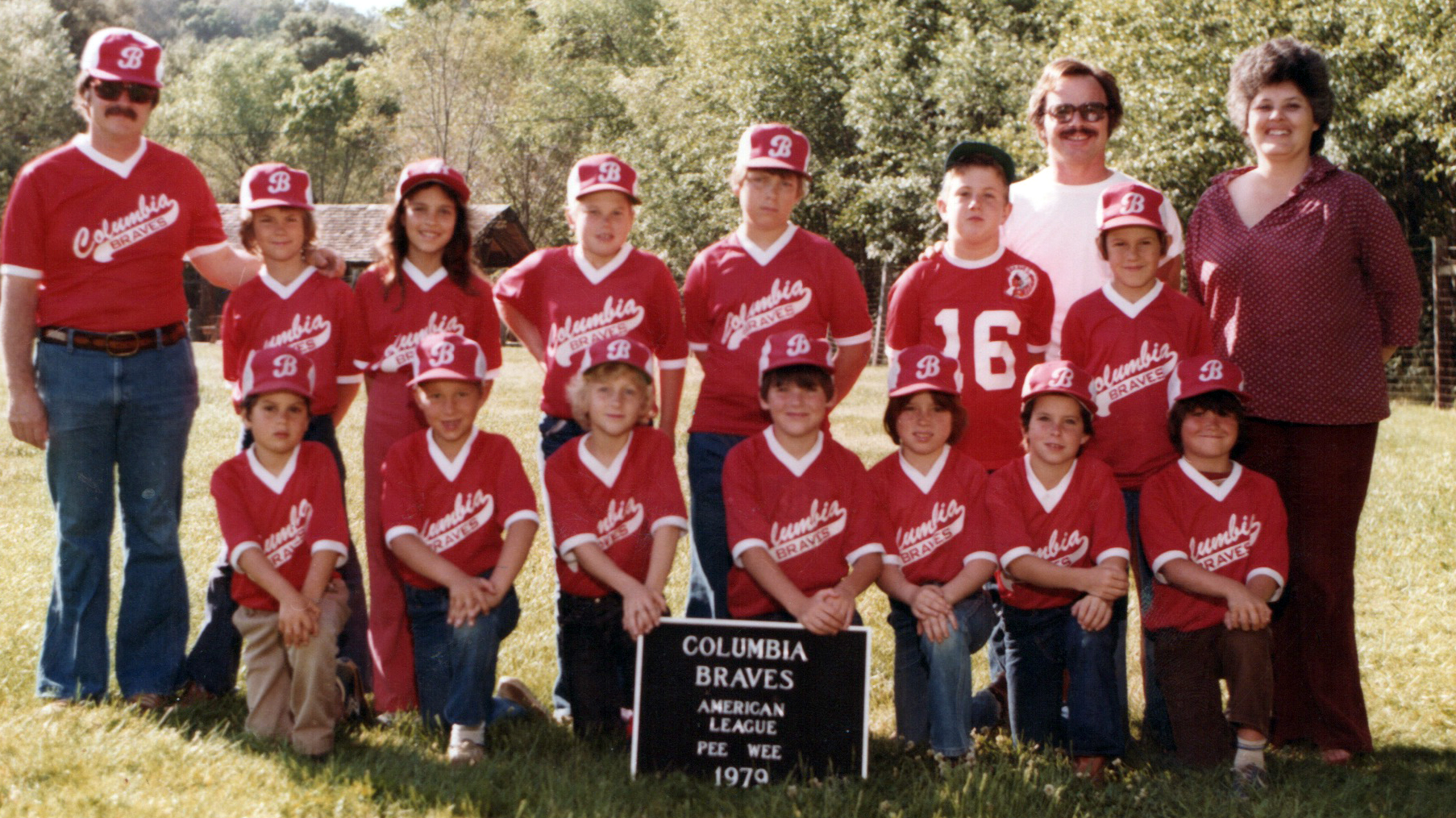

It took thirty years for me to realize that as a kid I had been judged an athletic misfit and filed away where I could do the least amount of harm.

My daughter’s softball league holds a draft every year to place the eligible players on several different teams, equally balanced by skill. And then I realized: My childhood team, so terrible that it won two games in four years, had been comprised entirely of the kids who couldn’t play very well.

I don’t recount this story here to elicit sympathy for my childhood self, or to judge the parents who devised this plan of attack (though they were selfish assholes), but to establish the fact that I am not, nor have I ever been, a jock.

I did not have a moment in high school where someone discovered that the nerdy kid with the bowl haircut could, miraculously, throw a football accurately or hit home runs or reliably plant a jump shot from outside. The closest I came to any of that was when a bunch of guys who hung out at the computer lab during lunchtime (which I did not, since I was too busy playing a dice-themed fantasy game instead) recruited me to be on their team in an inter-school programming contest.

That’s the nerd stereotype, right? Bad at sports. Loves computers. And probably spent his lunch hours playing Dungeons and Dragons. Except that the dice game I played in high school wasn’t D&D, but Sports Illustrated Superstar Baseball. Because I loved, and love, baseball. I even loved playing on that losing team of baseball misfits.

It was a long time before I realized that in the geek world, there’s a weird schism between the people who love sports and the ones who don’t. The first time I saw someone on Twitter act furious that one of the tech nerds they followed was tweeting about sports, I was amazed. These are people I otherwise felt a kinship with, as fellow lovers of technology and sci-fi and comics and similarly nerdy topics. But they had suddenly drawn a line between what was geek-appropriate and what wasn’t. And I was on the wrong side.

It’s easy to look at sports and view it as a massive jockocracy, a celebration of the physical over the intellectual, an industry designed to sell beer (and, later in life, Viagra) to high-fiving fratboys.

And yet sports are embraced by nerds as much as by jocks. The revolution in baseball chronicled in Michael Lewis’s book “Moneyball” was one driven by nerds with spreadsheets (and later, massive databases) who discovered an entire layer of baseball hidden in its statistics, one that could be turned to a team’s advantage. The most successful professional football coach of the past decade is a mumbly slob who wears hoodies with the sleeves cut off on the sidelines. And fantasy sports—a number-driven pursuit utterly disconnected from reality—is a multimillion-dollar sub-industry.

I’ve heard it said in more than one geek-oriented forum that sports are a modern manifestation of our base, tribal tendencies. That it’s more socially correct to cheer for the paid professionals wearing the home team’s laundry and boo the ones wearing some other set of colors. A statement like that might seem to suggest that geek culture is above such baser instincts, when of course geek culture is just as rife with tribalism. Whether you’re a Red Sox fan booing a Yankee or an Android fan posting angry comments at the end of an article about Apple or a “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” fan mocking the viewers of “Supernatural” or a Magic player who laughs at kids playing Pokémon, you’re someone who has identified with a side and demonized the opposition.

It’s a fact of human nature proven by endless wars, nationalist politicians, and the Stanford prison experiment. (As a fan of Stanford’s arch-rival, the University of California at Berkeley, I’d like to suggest that all the study proved was that Stanford is made of pure evil, but I think I’d just be proving its point.)

Geeks analyze (and over-analyze) everything. We want to know the rules of a system. We want to watch something repeatedly until we know it by heart, and have spotted all the flaws. We want to debate theoretical conflicts between incompatible objects, like the Death Star and the Enterprise or Superman and Spider-Man.

Enjoying a sport, at least at some level above tribalism, does require being able to analyze it. I admit that baseball is not everyone’s cup of tea, but when I ask why people don’t like it, most of them simply say that it’s boring. And viewed on one level, it most certainly is. If you spend hours watching a baseball game waiting for a run-scoring hit or, better yet, a home run, you will spend most of your time being disappointed.

And yet to me, the game unfolds into something much more interesting when you focus on the individual confrontation between pitcher and hitter—baseball being one of the rare sports where the offense doesn’t possess the ball. My wife, who was not raised around sports, became a baseball convert once she became aware of the strategy happening on a pitch by pitch basis. I admit, it’s still not a sport for everyone, but it seems to me that debating the right pitch selection when the count is 1-2 and there’s a man on third is not that different from debating the right decision to make in chess or Settlers of Catan or Halo.

Given my lack of athleticism, my history of being on awful teams, and the usual collection of high school locker-room horror stories, there are plenty of reasons for me (and other geeky types) to not be a fan of athletic competitions. Yet we are. Given that I could just as easily boo Windows users or DC comics readers as Dodgers, why do I like sports?

For a possible answer, I turn to my favorite novelist, Nick Hornby. In addition to being an award-winning writer, Hornby is an obsessive soccer fan who has written the definitive memoir about being a fan, “Fever Pitch.” (Read the book; skip both forgettable movies.) In his recent ebook, “Pray,” Hornby speculated that we are fans of sports because it provides drama that can not be predicted by any amount of analysis.

A match can’t be a work of art because there is nobody playing God. When you watch a play or a film, even a film directed by Tarantino or Hitchcock, you are aware, somewhere in you, that there are many, many people who know the ending… the people who willed it, wrote it, shaped it…. The glory of [the last day of the English Premier League season] was that all was chaos. Nobody in the world knew how it would turn out, and nobody — not the coaches, not the players on the pitch, not the referee, not the hundreds of millions watching around the world — could shape anything.

What sports give me, and my sport-loving comrades, is an opportunity to do the same, but in a world that has a fundamental amount of mystery that just can’t be reverse-engineered. Statistics reveal to me the true face of baseball, and (American) football affords me an enjoyable amount of game-theory analysis (or as it’s more commonly known, Monday-morning quarterbacking). But in the end, with sports there is never a point at which I can sum up what I’ve seen so far and figure out the ending that’s been scripted. Anything could happen. And I find that incredibly appealing.

Unless we’re talking about fans of wrestling. I mean, it’s totally fixed. Only an idiot would like wrestling. Let’s all go beat those guys up!

Jason Snell is editorial director at IDG Consumer & SMB, publishers of Macworld, PCWorld, and TechHive. Prior to that, he was editor-in-chief of Macworld for seven years. His projects outside of work include The Incomparable, an award-winning podcast about geek culture. He lives in Mill Valley, California, with his wife and two children.