In 2013, filmmaker, archivist, and erstwhile punk Stephen Parr toured the Packard Campus, the Virginia facility where the Library of Congress preserves audio-visual material, as part of a program organized by the Association of Moving Image Archivists.

Funded by a partnership between the David and Lucile Packard Foundation and the Packard Humanities Institute, and donated to the Library of Congress, the Packard Campus was rebuilt from a Cold War–era bunker that had stored currency intended to replenish the country’s cash reserve east of the Mississippi following a nuclear attack. The refurbished 415,000-square-foot facility opened in 2007 and consolidated the Library of Congress’s audio-visual collections, with 90 miles of shelving and 124 vaults for flammable nitrate film.1

On his tour of the facility, walking through the film archives of Bob Hope and Les Paul, Stephen Parr contemplated this vast collection as well as the archive of Oddball, his own film and video footage collection in San Francisco.

“Here’s this facility, and there’s maybe 140 people [working] there. I thought that’s probably smaller than the administrative staff at Twitter. That’s probably smaller than the accounting department at Facebook,” Parr remembers. “And I’m thinking where the priorities of our culture really lie.”

Like the Library of Congress, with its small band of preservationists, America’s independent stock footage entrepreneurs sit on troves of our country’s cultural history — from homemade porn to news outtakes. With the obsolescence of film and video equipment, compounded with limited budgets and ever-falling income from licensed materials, owners of small archives are making critical decisions about which moving images will make the leap forward into the digital era and which, like so many floppy discs, will join the graveyard of lost media.

Punk’s not dead

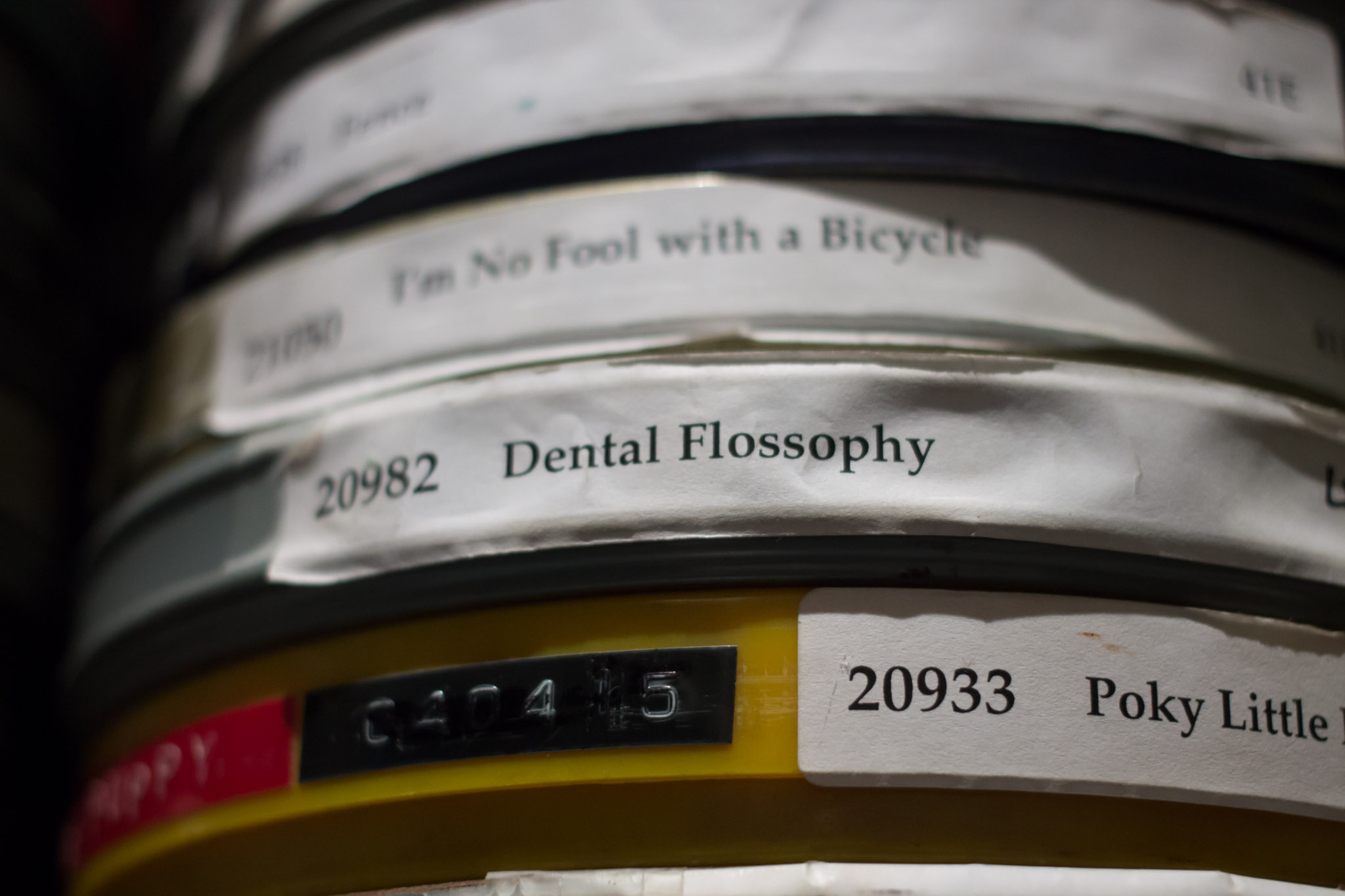

Visitors enter Oddball Film + Video through a furry black door crowned by a framed Ganesh. In three large rooms, film reels are stacked floor to ceiling, taped with catalog codes and titles like Human Values: How Friends Are Made, Dudin’, and Chicago: Midland Metropolis. The weight of the film on the floor is so great that Parr instituted a one in/one out policy: for every item that arrives, one must leave, to prevent the literal collapse of his empire.

The occasional design flourish points to an idiosyncratic mind. Vintage scales line the hallway to the bathroom. Near the back of the archive, two sewn-together sheets and a few rows of chairs constitute the screening room.

Here Parr and his curators exhibit works they’ve pulled from the archive, collecting them under themes that interest them — like a Valentine’s Day screening of venereal disease films, or a paean to strange robots that featured a clip of Elektro the Smoking Robot, made famous during the 1939 World’s Fair.

Parr’s work as a video artist preceded the creation of his archive in the Mission District of San Francisco. In the 1970s, he managed a number of event spaces across the country and shot video of musicians and artists he liked, including John Cale, the Ramones, and Allen Ginsberg. Parr also collected video and film ephemera, which he used to create video montages for art galleries and nightclubs.

When he was a young man, existing archives didn’t seem like an easy fit for Parr’s sensibilities. “Archives were super straight-laced, and other collectors were hobbyists, borderline fetishists, or hoarders. So I decided to build my own,” Parr said in an interview with Film Threat.

His first client was the director Ridley Scott, who arrived in San Francisco to film a beer commercial, saw one of Parr’s montages in a club, and licensed burlesque footage from him.

In the heyday of film and video, independent stock footage companies sprang from people like Parr — collectors who took a closer look at the materials they had compiled out of personal interest and began licensing footage for use in feature films, documentaries, and commercials.

Corporations such as Corbis Motion and Getty Images grew by purchasing smaller stock footage firms, but there remain a handful of independent companies, such as A/V Geeks, in Raleigh, and Los Angeles’s Budget Films. Budget was started by Al Drebin and is now run by his daughter, Layne. The storehouses of these companies reflect their owners’ predilections, from Eastern European avant-garde animation to peanut butter commercials.

Faster and cheaper

When Drebin launched his business, the unauthorized copying (pirating) of footage certainly existed, but the means to distribute films weren’t efficient. An article cites Drebin’s customers paying from $3 for a silent-film reel to $35 for a copy of the John Wayne feature Stagecoach.

“There are film fanatics who are as hooked on movies as some people are on dope,” Drebin said in a 1972 interview. Projected films seemed special, and viewers arranged to borrow reels to present at social clubs and events.

With the turn toward digital media, stock footage companies face the demands of shorter expected delivery time and lower fees. Corbis and Getty sell digital stock footage and features to the same clients as Parr and his colleagues. These larger companies make it easy for buyers to search tens of thousands of digital clips and toss matches into a virtual shopping basket with an instantly calculated price that depends on licensing terms. It might cost $599 for film festival use of a 1945 bowling clip, or $2,399 for including in an ad part of a 1952 propaganda film about the “Soviet robots” produced by the Communist education system.

Potential clients can preview 800,000 clips on Corbis Motion’s site and filter a search by format, broadcast standard, shot type, duration, and other modifiers. Hit a bump, and a specialist can instantly chat through the browser. The breadth of choices and ease of selection make purchasing a clip nearly effortless.

Smaller stock specialists operate with fewer bells and whistles. Call Oddball for help on a project, and chances are that Parr himself will pick up the phone. Because much of the collection isn’t digitized, the searchable database doesn’t link to clips; instead, it has sometimes-inscrutable written descriptions, like MS Short dark haired girl removes bra. MS she is posing next to the mirror. Cu she takes a TV tray that says “Nipponese” and makes it say, “Nip on these.”

These smaller companies are connoisseurs who love their product and deeply understand the needs of their customers. When presented with a request, they determine context and taste, and they may suggest alternate solutions that approach a filmmaker’s question with an unexpected but compelling answer rather than a list of results matching filtering criteria. The work is, as Parr says, “more cultural than technical.”

For this reason, a filmmaker of a certain type seeks out Parr and his team. Filmmakers Gus van Sant and Spike Lee, as well as the makers of the documentaries Weather Underground and Room 237 (a film about the meanings embedded in The Shining) have hired Oddball. For these films, as well as for numerous PBS documentaries, episodes of MythBusters, and other shows, Parr and his team consult with the producers to pull clips of mad scientists, scheming harlots, plane crashes, aluminum factories, and peach de-fuzzing machines.

The volume of licensing requests determines which materials will be digitized. Nearly all materials are delivered digitally, a change from even five years ago, when it was still common to send sample reels with the understanding that recipients had the equipment and skill to play them.

Parr’s team prioritizes digitizing materials that seem particularly valuable or useful, but customer demand triggers the process. Oddball has several films on deaf culture; because they’ve never been requested, none have been digitized. And good luck to the unlabeled film negatives that have yet to be printed. They may be gems, duplicates, or riddled with technical errors; it’s possible that most will degrade or be disposed of before anyone can judge.

At the Exploratorium

Light, film, magic

On a March night at Pier 17, the twinkle of buildings on the hills of Chinatown and North Beach is almost painterly, but visitors focus instead on a projector set up inside a small wooden structure. Parr worked with a local science museum to project film onto fog as an outdoor exhibit for an after-hours event targeted at 20- and 30-somethings, a complement to the Fog Bridge installation by artist Fujiko Nakaya. This show comes with props: the event organizers supplied the audience with large white poster boards to capture the projection, allowing individuals to function as part of a moving screen.

Something about a projected filmstrip proves intoxicating, roped with sentiment for those who recall the sound of the strip clicking into place as a pause from lectures at school: those lazy days as summer approached when the lights were switched off and the classroom cooled down. Some of the event’s older visitors arrive early and grab bench seats before the show starts. Later, attendees jostle for position as they try to determine the best angle for viewing the show.

The younger people in the crowd have likely never seen a projected classroom film, and this showing may have the scent of vintage appeal, like record players and Polaroid photos. Many of Parr’s acquisitions came via schools eliminating their stores, but that sourcing has slowed, as few schools still own any film equipment. Being here to watch a filmstrip feels like an echo — or even a séance.

Audience members reflect the film.

The show begins and the projection speaks through a cloud of fog, breaking up into pink, blue, and yellow light that takes form when the F-100 machine pauses between 15-second-long puffs of fog.

The first of three filmstrips concerns cell biology. Audience members pick up the white poster board panels and hold them aloft, connecting and disconnecting, shifting the panels to capture the dance of single-celled organisms projected through the fog.

Photos by the author.

-

Editor Glenn Fleishman wrote about his visit to the Packard Campus and the particular issues of audio archiving and distribution rights in Issue #4 (Nov. 22, 2012): “The Sound of Silence.” ↩

Colleen Hubbard lives in England, where she writes fiction and nonfiction.