Portland, Oregon, is the largest city in the country that does not add fluoride to its water. And, following a fluoridation measure that failed in late May with 60 percent of voters opposed, it’s going to stay that way.

Let’s just get the obligatory hipster jokes out of the way: “Hope you like drinking PBR through a straw!” “What’s next, artisanal hand-crafted dentures?” “That’s what happens when your dentist is also your barber!” “Hey, ironic tooth decay looks great with your handlebar mustache!” “Nothing like cruising on your fixie, feeling the wind between your teeth.” “Put a bird on your wooden tooth!”

Okay, that last one needs some work. Can we move on now?

Brushes with conspiracy

Portlandia jokes are hard to separate from the issue at hand, because many of the reasons my home city chose to reject fluoridation — something the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) calls “one of the 10 great public health achievements of the 20th century” — are rooted in the very attitudes Carrie Brownstein and Fred Armisen parody on their IFC sketch show.

Naturopaths fret that fluoride would negatively affect patients with chemical sensitivities; environmentalists worry about the state’s already imperiled salmon population; and iconoclasts of every stripe are reluctant to fill the public water supply with an additive they think could be better distributed through other means. In other words, the anti-fluoride lobby looks like the city itself: a cross section of concerned parents, environmentalists, community leaders, and total hippie nut-jobs.

While fluoride is found naturally in some water systems, there’s none at all in Portland’s water supply, which comes from rain and snowmelt in the 102-square-mile Bull Run watershed. (The water is treated with ammonia and chlorine, however.) Reluctance to contaminate our water supply was high on the list of reasons why fluoride was voted down, as Portlanders were reluctant to add more “chemicals” to a relatively pure water supply — and it’s true: our tap water is excellent.

According to the American Dental Association (ADA), fluoride’s benefits are both topical and systemic: fluoride rinses and toothpastes help to remineralize tooth enamel, and ingested fluoride strengthens developing teeth. Adding fluoride to the water supply ensures that everyone has equal access to these benefits, regardless of income or how good your parents are at being parents. It’s regarded by many as a simple, common sense public health measure, but common sense was in short supply in Portland’s recent campaign.

Debate over water fluoridation was snappish and heated, thanks in part to the Portland City Council’s September attempt to push fluoridation through without putting it to a vote. (Conspiracy theorists: Activate!) Opponents gathered enough signatures to put water fluoridation on the ballot, and subsequent months saw an escalating public debate featuring protesters on street corners, yard signs stolen and vandalized, and blog comment threads destined to become the stuff of local legend.

Staunchly “pro-science” fluoride supporters waved the flag of endorsements from the ADA and the CDC, while front yards across the city sprouted signs urging “No Fluoridation Chemicals” and questioning the wisdom of adding “drugs” to the region’s water supply. By the time the actual vote rolled around, the phrase “can we please not talk about fluoride?” had become a common refrain in polite company.

Setting aside the fringier elements of the conversation — the people who think fluoride is a government plot to control the population by keeping ’em dumb — it’s rare to see Portland so deeply divided.

Portland exceptionalism

This wasn’t the first time Portland has put fluoride to the vote: it was rejected by voters in 1956 and 1962, passed in 1978, and was then promptly repealed in 1980. Opposition to fluoride, authors R. Allan Freeze and Jay Lehr pointed out in their book The Fluoride Wars, tends to mirror the prevailing paranoia of the age: In the 1950s, people worried about communist plots; in the 1970s, opponents worried about the environment.

Meanwhile, in the rest of the country, fluoridation kicked off in 1945 in Grand Rapids, Michigan, and continued apace. By 2012, 73.9 percent of the US population with access to community water systems received fluoridated water, according to the CDC.

The list of organizations endorsing fluoride in Portland is long, from the aforementioned ADA and CDC to the editorial boards of every newspaper in town, including the homeless advocacy paper Street Roots, the Oregonian, and the weekly newspaper where I (full disclosure!) work as an editor. On the anti-fluoride side are interests ranging from local branches of the NAACP and the Sierra Club to the People’s Food Cooperative and the Oregon Association of Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine.

In a recent blog post, respected Portland ad exec Jelly Helm laid out his reasons for voting against fluoride, based on his own research and interviews with both pro- and anti- fluoride advocates. He concluded,

Portland has been resisting fluoride for years and years. We are the last big holdout in the US. We’re either idiots — crackpots who won’t listen to science — or people who believe that our ethos demands that we ask deeper questions and create our own solutions and processes to accomplish our shared goals.

Pro-fluoride advocate and dentist Virginia Feldman expressed a similar sentiment in an interview, albeit more critically. “I do think Portland is one of the best places in the US to live — but we are so in love with ourselves!” she says. “We want to keep Portland weird — as defined by ‘like nobody else.’ Many see Portland being the largest city without fluoridation as a feather in our cap.”

Sensible non-experts

About a month ago, The Magazine ran an article in which physician Saul Hymes argued that in order to better persuade patients that vaccines are effective, doctors need to learn how to tell stories that turn dry facts and figures into a compelling, often personal story. It’s advice physicians in Oregon might take note of, given that Oregon currently has the dubious distinction of having the highest rate of unvaccinated kindergartners in the country.

Anecdotal evidence, though, is exactly what doesn’t help in situations like the one in which Portland has been embroiled for the last few months. First-hand accounts abound: Someone’s neighbor grew up with fluoride, but still has 14 cavities. Someone else is pretty sure her thyroid cancer is fluoride related. And the hippie down the street is worried fluoridation might cause her third eye to close forever. (I sincerely wish that last part were a joke.) Much of the discourse around fluoridation is personal — literally inside your head personal.

If doctors need to learn to communicate more effectively using personal stories and anecdotes, the general public needs to consider which stories they’re listening to. Dr. Michael Freeman, a professor of epidemiology at the Oregon Health and Science University, says that when trying to parse a complex health issue, “You should ask people you trust whose perspective makes sense.” In other words: Ask a dentist. Don’t ask the local adult marching band.

The problem, of course, is that “9 out of 10 experts agree” isn’t particularly compelling to a populace weaned on Lies My Teacher Told Me. There are plenty of historical examples to back up the belief that the government medical authorities don’t always know best. (Tuskegee syphilis experiments, anyone?) A predisposition to questioning authority leaves people wide open to arguments that fluoride is an industrial waste product or a fish-killing poison or the result of a vast, sinister conspiracy. (Never mind that no one has convincingly outlined who, exactly, would benefit from a pro-fluoride agenda — the dentists who overwhelmingly support fluoridation would seem to have the most to lose.)

It is this argument more than any other that rings true to me, and explains why Portlanders overwhelmingly rejected water fluoridation. It is not that people don’t believe that fluoride is effective; many do. It is that they are not going to take an expert’s word for it — they’re going to do their own investigations, come to their own conclusions, and resist bowing to the conventional wisdom. Noble goals all, until you realize what a Pandora’s box of crackpottery is opened just by Googling the word “fluoride.”

Dr. Freeman, who’s an experienced advocate for the efficacy of vaccines, cautions against a “paternalistic view of ‘I know what’s best for you because I come from science.’” Resistance to certain health measures “cannot be boiled down to ‘Oh, they’re just a bunch of nuts in Portland,’” he says. “People have legitimate concerns. I think the more we can avoid that sort of conclusion, the better we’re going to be doing for the people who are consuming healthcare.”

I voted for fluoride, but I never joined my Richard Dawkins-quoting friends in railing against Portland’s anti-science tendencies. In the same way that I’m not going to tell someone with cancer that she’s fooling herself if she thinks eating a pomegranate is going to help, I’m not going to tell concerned parents that they’re wrong to worry about their kids, even if I disagree with their conclusions. I am, however, going to make my decisions based on what the experts have to say, and encourage others to do the same. As Mark Lynas put it in a recent speech about GMOs (a conversation Portland is definitely not ready to have), “If an overwhelming majority of experts say something is true, then any sensible non-expert should assume that they are probably right.”

On behalf of sensible non-experts everywhere: I guess my future kids will be taking fluoride supplements.

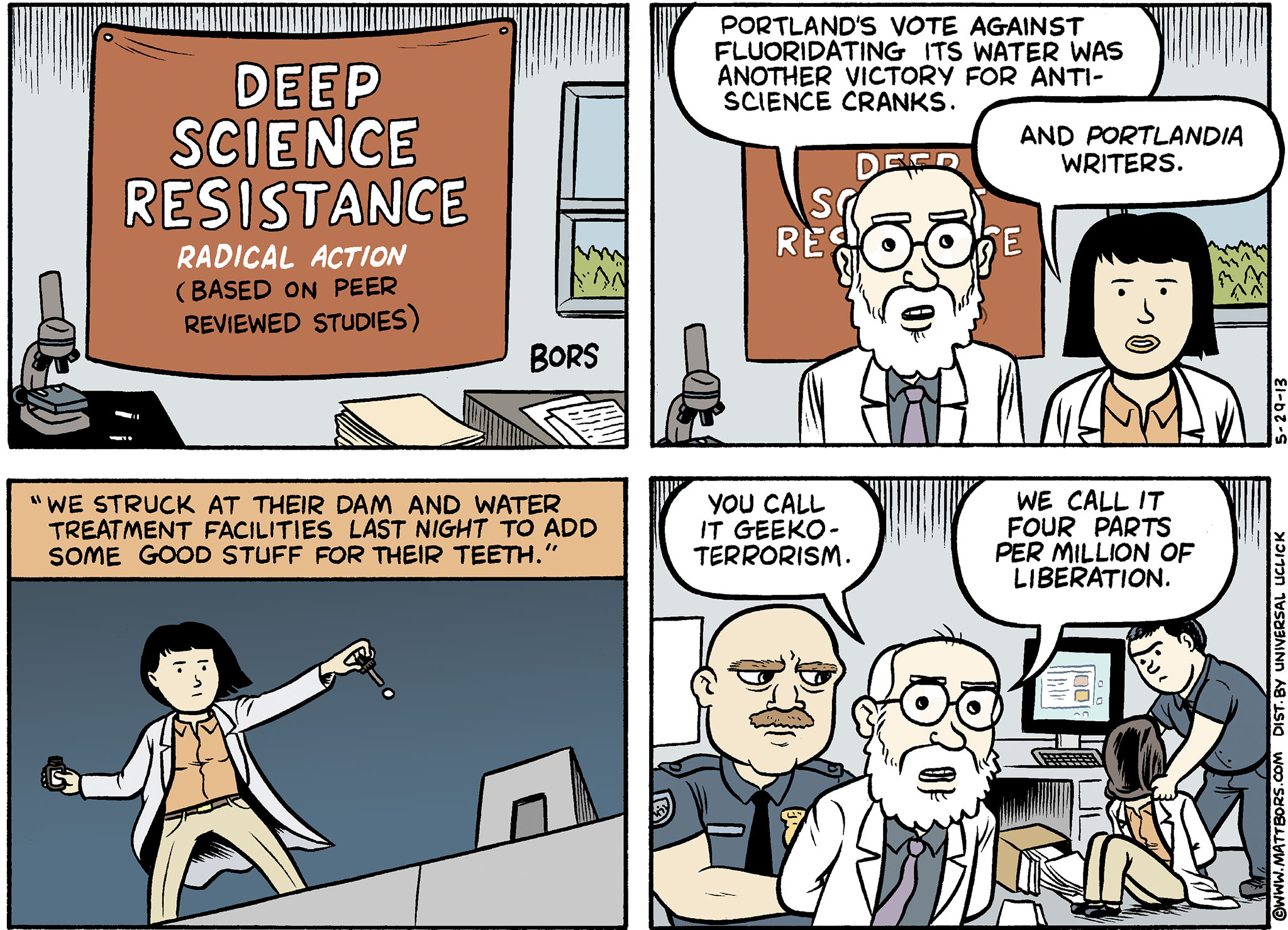

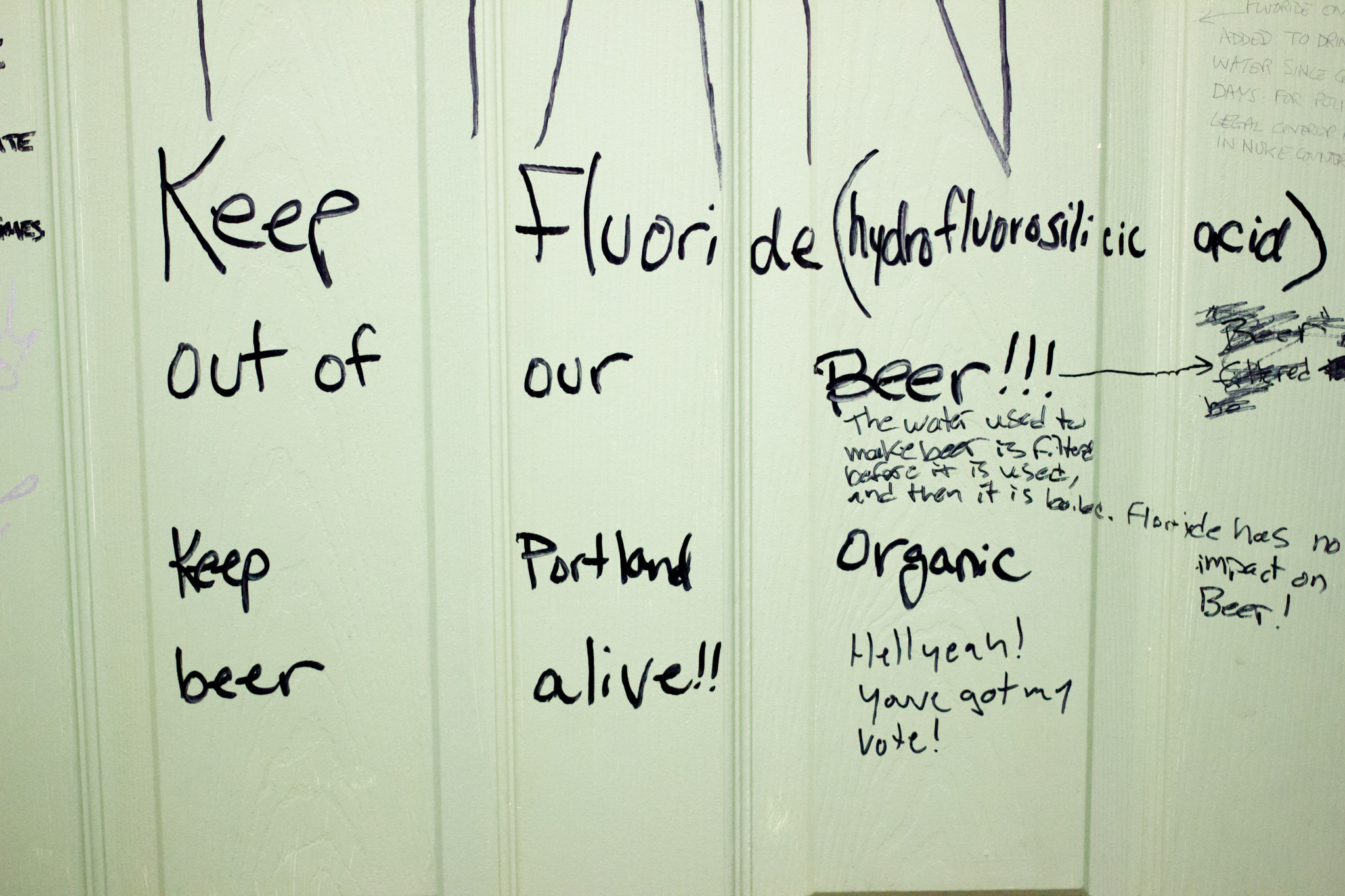

Photos by Pat Moran.1 Illustration by Matt Bors.2 BORS ©2013 Matt Bors. Dist. By UNIVERSAL UCLICK. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.

-

Pat Moran is a photographer from Portland, Oregon, whose work can be seen at patmoran.tumblr.com. He is also an actor, producer, and company member at Action/Adventure Theater. ↩

-

Matt Bors is a political cartoonist, editor, and illustrator in Portland, Oregon. His latest book is Life Begins At Incorporation. ↩

Alison Hallett is the arts editor of The Portland Mercury, an alt weekly in Portland, Oregon, as well as the co-founder of Comics Underground, a quarterly reading series that showcases Portland's thriving comic book scene.